A new study claims palbociclib, an approved breast cancer drug, can treat an aggressive form of the cancer, bringing hope to thousands of afflicted women in the UK.

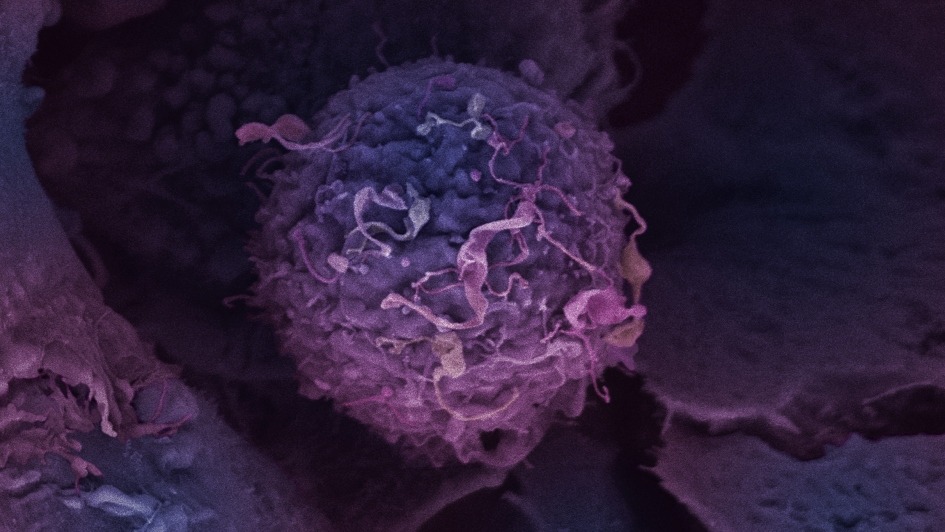

Image: Breast cancer cell. Credit: Anne Weston/Francis Crick Institute

Subscribe to our email newsletter

As per the study which was published in the journal Cancer Research, the clinical trial showed positive results of the drug palbociclib in a specific type of triple negative breast cancer.

Researchers at the Institute of Cancer Research, London, funded by Breast Cancer Now reportedly identified a defect in some triple negative breast cancers linked to poorer outcomes for patients and a drug that targets the outcome of this defect.

According to the study, the palbociclib, which is used for treating other breast cancers spreading to a different part of the body, can also be used for treating nearly one-fifth of the people with triple negative breast cancer.

Such a discovery is expected to bring a sigh of relief for women needing targeted treatment, as there is high chance that their cancer could spread sooner, becoming incurable and often resistant to traditional chemotherapy.

An assorted group of breast cancers, the aggressive triple negative breast cancer lacks the three molecules normally used for categorising the disease, including the oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).

The molecules have been used for cultivating a range of targeted treatments for other types of breast cancers. But absence of these molecules in triple negative breast cancer can mean that treatment options are limited for this group of breast cancers. As a result, such cancer is usually treated with a combination of chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy.

Every year, in the UK alone, about 55,000 women are diagnosed with breast cancer out of which over 8,000 cases emerge as triple negative. This type of cancer tends to disproportionately affect younger women and black women.

The research led by Rachael Natrajan, at the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) found a way to identify triple negative breast tumours that could be more likely to respond to a class of drugs CDK4/6 inhibitors, including palbociclib.

As part of the study, the research team screened 200 frequently altered genes in breast cancer to investigate how gene changes affect the cancer’s ability to grow.

Using lab grown tumours that mimic tumour growth in a human body, the team found that triple negative breast cancer cells with alterations that caused a decrease in the levels of protein called CREBBP, could grow quickly and more aggressively.

The team then drew on two large patient databases for further investigation into what happens when CREBBP levels are low in the tumour and found that the correlation resulted in poorer survival rates for patients suffering from triple negative breast cancer.

Moreover, low levels of this protein are also found in various other cancer strains such as uterine, ovarian, and some lung and bladder cancers. This suggests that the protein is essential for the growth of the tumour.

When CREBBP protein levels are low, the tumour cells find an alternate way of multiplying by relying on two proteins termed as CDK4 and CDK6.

These proteins can be blocked with a group of drugs known as CDK4/6 inhibitors. Palbociclib is a CDK4/6 inhibitor, which is presently being used for treating some secondary breast cancers in the UK.

The Institute of Cancer Research Functional Genomics team leader Rachael Natrajan said: “Our study shows what drives the growth of some triple negative breast cancers and suggests the exciting possibility that an already-approved breast cancer drug could be used to help women with this type of disease.

“Our findings were only possible because we used an innovative model, involving the growth of 3D ‘mini tumours’ in the lab, to more closely reflect how tumours develop in the body.”

Advertise With UsAdvertise on our extensive network of industry websites and newsletters.

Advertise With UsAdvertise on our extensive network of industry websites and newsletters.

Get the PBR newsletterSign up to our free email to get all the latest PBR

news.

Get the PBR newsletterSign up to our free email to get all the latest PBR

news.